Nilaya’s innovative Featherlight construction technique is designed to be lightweight, stiff and very competitive in regattas, without compromising the comfort and low noise levels associated with Royal Huisman yachts

The bar was set extremely high for the 47-metre (154ft) Nilaya, Royal Huisman’s most recent yacht, which has just been Christened at Het Scheepvaart museum (the National Maritime Museum) in Amsterdam. The last yacht to bear that name was a 34-metre (112ft) full carbon sloop that combined a very high level of performance with ocean cruising capability, striking good looks and a luxurious interior. A game-changer on the superyacht racing circuit, in the 13 years since her launch that boat has won almost every race she entered… and she has done a lot of racing.

While many aluminum vessels have some composite parts, Nilaya is much more a hybrid

It’s not surprising, then, that the new Nilaya has a fair amount in common with her namesake in terms of general concept, proportions and aesthetics. She is drawn by the same design team of Reichel/Pugh and Nauta, even more elegant and built on a substantially larger scale, with no compromise made in her racing ambition. However, the design brief also put a greater focus on long-distance ocean cruising, with more emphasis on considerations such as impact resistance and ease of repair in remote parts of the world. Thus, despite some similarities – profile, straight bow, wide transom, twin rudders and so on – the new Nilaya is actually a significantly different beast.

One key difference is the hull. Rather than carbon, it’s mostly aluminium. But this isn’t the sort of aluminium that’s typically used in large yacht construction, it’s Alustar – a premium grade alloy with 20 per cent more tensile strength. And this is, strictly speaking, a hybrid build with a lot more carbon components and structures than one would expect to find in an aluminium cruiser-racer, even one that is focused on high performance. Royal Huisman’s sister company Rondal is of course a world leader in marine carbon fibre fabrication and the Nilaya project benefits from the inherent synergy between them. Why not build the whole yacht in carbon? ‘The owners wanted a powerful performer with easy-to-helm responsiveness, basically all the good habits of their last boat but with more comfort and less noise,’ says Nigel Ingram of MCM Newport, the owners’ representative for the build. ‘Alustar is the right material for an advanced, top quality superyacht for global cruising. It deals with noise better [than carbon] and is a better choice for cruising in comfort to remote locations. However, we also thought it was possible to build a lighter aluminum highperformance superyacht. Royal Huisman was not afraid to invest in research to explore and develop all manner of innovative weight-saving possibilities. They really chased the details.’

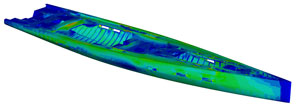

The variable spacing of frames in Nilaya’s hull was calculated and optimised with in-houe FEA software

The design process in detail

The Nilaya project began with a general concept developed by Nauta Design, which set the key parameters for the shipyard, the naval architects and the other key players involved. ‘We asked ourselves a very simple question,’ Nauta’s co-founder Mario Pedol explains. ‘Could we design an aluminum yacht that was much closer in terms of displacement to an equivalent carbon boat? The answer was yes, following my intuition that hull and deck are only 15 per cent of the total weight of a modern sailing yacht. This was backed by analysis of our most relevant projects from our designs.’

‘In this process we took into account the owners’ priorities including less noise, the strength of the material and the possibility of repairs around the world. We set about discovering ways to minimise the difference [between aluminium and carbon] and to look for advantages elsewhere. Royal Huisman supported this vision with enthusiasm and accepted the challenge.’ After the concept came the detailed naval architecture with Reichel/Pugh working alongside one of the world’s leading CFD consulting teams, Caponnetto Hueber. Giorgio Provinciali who brought about 20 years’ worth of America’s Cup experience to the project. Top performing designs in both aluminium and carbon were made into models for tank testing.

Beyond conventional CFD analysis, the design team also conducted a sophisticated RANS code analysis – a method more commonly used to optimise the shape of submarine hulls – to predict underwater turbulence generated by the hull, keel, rudders and propellers. They then collected extensive wave data from the owners’ favourite windy cruising grounds and developed new hull shapes to run through the RANS CFD code to improve the seakeeping and motion characteristics of the yacht under sail and power.

Meanwhile, the design loop for the aero package was also under way with Reichel/ Pugh working alongside Doyle Sails and Rondal, who designed and built the yacht’s integrated sailing systems as well as her spars. ‘Bringing in the mast and sail designers early in the process has significant advantages,’ Jim Pugh says. ‘From the aero CFD side, Rondal and the sail designers shared high-quality data about sail forces and sail loads that we integrated into the hydro CFD studies of the candidate hulls. This markedly improved the quality of the CFD hull testing and the resultant performance prediction. The mast and sail loads were then input into the hull and deck’s structural engineering.’

Nilaya’s VPP promises a level of performance that will challenge the leading yachts on the superyacht racing circuit, with boatspeed exceeding the true wind speed on a close reach in a 10-knot breeze under mainsail and jib alone.

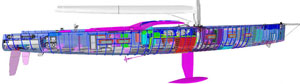

Royal Huisman’s in-house 3D engineering and weight management is comprehensive and extends to lighting, insulation, and all mechanical systems

Throughout the year-long design process the overall plan for the yacht hardly changed, John Reichel says, except that the hull became one metre longer with the extra length distributed mostly at the ends. ‘Weight distribution is critical for assuring comfortable motion on a cruising yacht,’ he explains. ‘We gave the shipyard team a weight study early on, not just for the total but for balance and maintaining the proper centre of gravity. Royal Huisman responded with extensive Excel sheets showing the weight of every element. That’s a process typical of the highest-end racing programme construction.’

The deck plan was also developed with great attention to detail, ensuring that the layout works equally well for both cruising and racing. Royal Huisman built a 1:1 mock-up of the entire aft half of the yacht to fine-tune all the aspects of this dualpurpose functionality from sail controls and steering pedestals to the dining table, the seatback angles of the sun loungers and the steps from the sail-handling cockpit to the lounge area on the aft deck, leading to the bathing platform. Sightlines over the coachroof from the helm positions received critical attention and the fullscale mock-up was tilted to simulate typical heeling angles under sail in a range of conditions.

Nilaya is the first yacht built according to Royal Huisman’s new Featherlight method, which aims to narrow the gap in stiffness, displacement and thus performance between aluminium and carbon yachts. Described by the shipyard as a holistic process rather than a specific set of building techniques – ‘not a single process or construction material, but an integrated, multi-disciplinary approach focusing on weight reduction through advanced construction technology’ – Featherlight puts a strong emphasis on finite element analysis (FEA) and parametric modelling to achieve a wide range of gains in structural engineering. ‘Royal Huisman used FEA of Nilaya’s 3D model to fine-tune the engineering to a much higher level, adjusting plate thickness in the computer and predicting longitudinal stiffness or deflection,’ naval architect Jim Pugh explains.

Royal Huisman has made a major R&D investment in its Featherlight technology, which the shipyard regards as an important step in the evolution of its own DNA. It has developed its own in-house software tools for parametric modelling, which enables its design office to determine precisely the right thickness of any construction material for any location to achieve the design parameters. This empowers them to make smart decisions regarding, for example, the relative merits of aluminium and carbon in any structural application. It also allows them to design and optimise composite structures and components, in which carbon and aluminium are bonded together. Featherlight construction can also involve gluing aluminium components to each other rather than using fasteners.

The last time Nilaya appeared in Seahorse (February 2022 issue), halfway through her build, she was known only by the enigmatic code name Project 405 and already her ambitious weight saving targets were generating a fair amount of interest. Now completed and launched, those targets have been fully achieved and her displacement is 11 per cent lower than a yacht built to the same design by the usual methods. How was that achieved? Like a racing yacht build, continuous weight monitoring is a crucial part of the Featherlight process with a dedicated weight engineer assigned to the project from start to finish. Reichel/Pugh and Nauta Design worked with Royal Huisman on a daily basis throughout the design and build, jointly overseeing the weight study.

An overall weight target was agreed and every aspect of the build was given its own weight budget. With integrated teams exploring all the elements of the boat concurrently, everyone was aware of how each decision impacted others. Suggestions for improvements were shared and analysed in real time. For example, by a taking critical look at the high-voltage air conditioning (HVAC) system and selecting direct expansion and fan coils for each room, the total weight of the yacht’s hotel systems was reduced by 600kg. Rondal, meanwhile, managed to reduce the weight of the sailing systems significantly (see pages 82-83).

The completed yacht was transported from Royal Huisman’s HQ at Vollenhove to its Amsterdam facility for launch and seatrials

Conventional materials for reducing noise and vibration, such as foam panels lined with lead, add a lot of unwanted weight. To stay within Nilaya's interior weight budget, Royal Huisman made extensive sound attenuation studies and developed sophisticated composite panels using cork, foam, honeycomb and other materials. The owners were offered three options for the yacht’s interior cabinetry with different levels of weight, sound insulation and finish.

Royal Huisman also developed a “tribrid” propulsion system that provides three ways of powering the variable-pitch propeller and offers emergency ‘get home’ propulsion without the need for a separate third engine and gearbox. That alone saved two tons. Every incremental reduction in the yacht’s displacement in turn reduces the amount of power required for motoring, so the engine itself can be lighter and the engine room smaller, leaving more space for accommodation inside the hull.

‘I am proud of the investment we have made in advanced engineering and of the way teams from Royal Huisman and Rondal advanced new solutions to meet the brief from very knowledgeable clients and designers,’ Royal Huisman’s chief executive Jan Timmerman says.

‘Nilaya's owners also deserve congratulations for pushing everyone to achieve just a little bit more and for encouraging innovation at every step. Nilaya will be the world’s lightest aluminum sailing superyacht for her length; she rewrites the script for highperformance superyachts.’

Click here for more information on Royal Huisman »

We invite you to read on and find out for yourself why Seahorse is the most highly-rated source in the world for anyone who is serious about their racing.

To read on simply SIGN up NOW

Take advantage of our very best subscription offer or order a single copy of this issue of Seahorse.

Online at:

www.seahorse.co.uk/shop and use the code TECH20

Or for iPad simply download the Seahorse App at the iTunes store