Seagrass may be all prevalent in many popular anchorages but that does not make it invincible

When a yacht drops anchor in a seagrass meadow and leaves a divot, or an outboard motor propeller makes a scar, how long does it take for the seagrass to grow back? A lot longer than you probably think. Neptune grass in the Mediterranean, turtle grass in the Caribbean and similar species around the world are the redwoods and oaks of marine ecology: they’re extremely slowgrowing and can live for thousands of years. When damaged, they take decades to recover – or they might never grow back at all. However, they can be restored and 11th Hour Racing is funding some groundbreaking work in this field.

Seagrass propagates mainly by growing its rhizomes in a mat that spreads out just a few inches beneath the sea floor. If a hole is made a bit deeper than that, the seagrass can’t regrow unless the hole is filled in with sand or sediment brought by waves or currents. But quite often waves or currents can make the hole bigger. What starts as a small divot soon becomes a huge crater as the edges of the substrate under the mat of rhizomes are eroded and washed away, leaving an entire meadow of seagrass much more vulnerable to the next storm.

Anchors and outboard motors do a lot more damage than most sailors imagine. But a severe storm can wipe out an entire ecosystem, driving large pieces of flotsam – trees, parts of buildings, boats ripped from their moorings – across seagrass meadows, carving long, deep scars that just get bigger over time. That’s what happened in Puerto Rico in 2017 when two category five hurricanes, Irma and Maria, destroyed great swathes of seagrass and mangroves.

Why should we care about marine plants and trees in the wake of a natural disaster that kills thousands of people and wrecks the homes and livelihoods of many thousands more? Because seagrass and mangroves, like salt marshes, are natural storm protection barriers that absorb huge amounts of wave energy and prevent coastal erosion. They also play a crucial role in maintaining water quality and support the lifecycle of fish species that communities and entire nations rely on for food.

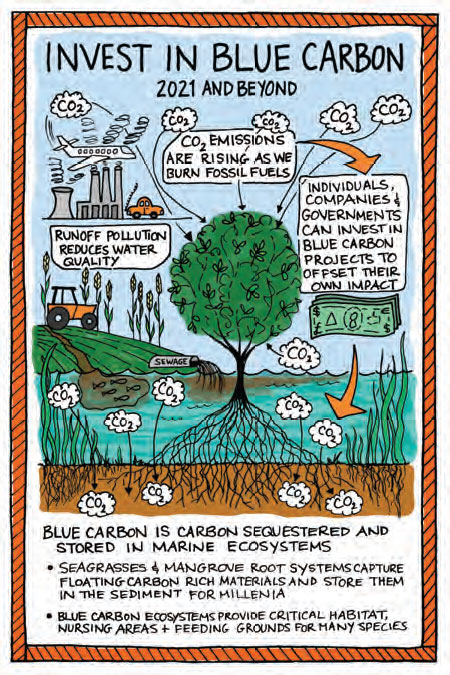

There’s another big-picture reason for all of us to care. While science points clearly to manmade climate change as a major cause of the increase in severe weather events that we’ve witnessed in our lifetimes, it also identifies coastal wetlands as one of our best solutions for confronting and curbing climate change. Together, healthy seagrass and mangroves form a ‘blue carbon’ ecosystem, also known as carbon sinks, that can store up to 10 times as much carbon per hectare as a forest on land. But the reverse is also true. When blue carbon ecosystems are degraded, they release similarly huge amounts of stored carbon back into the atmosphere – and right now, in most parts of the world, they are in sharp decline.

Slow-growing seagrasses like Thalassia (turtle grass) and Posidonia (Neptune grass) store far more blue carbon than their own weight, sequestering it in the substrate. Mangroves do the same and also store large amounts in their trunks, roots, limbs and leaves. Restoring them not only mitigates against some of the worst symptoms of climate change, like flooding and erosion, it also helps to combat the root cause. On top of all the obvious benefits for local ecosystems and communities, seagrass and mangrove restoration projects can, if done right, offer organisations and individuals an effective way to offset their carbon footprint on a voluntary basis.

To compensate for the carbon generated by the Vestas 11th Hour Racing sailing team during The Ocean Race 2017-18, 11th Hour Racing has been collaborating with The Ocean Foundation on blue carbon projects in Puerto Rico. They used The Ocean Foundation’s Seagrass Grow Calculator to convert the team’s carbon footprint to an approximate dollar value. ‘We have retrospectively increased our investments to include onsite training for the local community to fund the education programme around blue carbon certification. This is important to us as we have a net positive approach for our team, a determination to leave a restorative impact in our wake, both environmentally and socially,’ says Damian Foxall, sustainability manager, 11th Hour Racing Team.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, The Ocean Foundation and its local partner Conservación Conciencia identified Jobos Bay on the south coast of Puerto Rico as a suitable site for seagrass restoration. Crucially, all of the necessary infrastructure was already in place to make the project viable. The western part of the bay is managed by the Jobos Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, with staff who were keen to restore their seagrass meadows but lacked the additional resources to do so. One of the Foundation’s go-to seagrass restoration experts, Manuel Merello, had restored a patch of seagrass in Jobos Bay 10 years prior, so proof of concept was already established. ‘All the pieces were in place,’ says Ben Scheelk, The Ocean Foundation’s programme officer leading the Blue Carbon initiative. ‘And that’s essential. To work on public land, you need a permit from the US Army Corps of Engineers and they won’t issue a permit unless the people doing the work are credible.’

Restoration work started in 2018 and the simple, low-cost method of seed dispersal was swiftly ruled out. Thalassia seeds have a very low germination rate and it just wouldn’t work in such a large area. ‘Given the scale, we needed a more labourintensive but efficient approach called modified compressed succession,’ Scheelk explains. ‘To repair a hole or scar, first we bring in biodegradable sediment bags – sometimes hundreds of them – and stack them in the hole to re-grade the surface. The real issue is to get the edges repaired. If they’re too steep, the seagrass can’t grow.

Above: seagrass and mangroves combine to form a blue carbon ecosystem that not only mitigates against some of the worst aspects of climate change, such as flooding and erosion, but also helps to combat the root causes. People and organisations can invest in blue carbon restoration projects to voluntarily offset their own carbon footprints.

‘Then we take fast-growing pioneer species like shoal grass or manatee grass from a donor bed, wrap them around a metal stake and put these planting units in the sediment bags. They quickly spread, stabilise the sediment and prevent further erosion. This creates the right conditions to allow the climax species, Thalassia, to overtake them in time. We’re speeding up what nature would do over many decades, compressing that into five to ten years.’ Bird stakes – PVC pipes with wooden perches on top – are then placed in the seagrass to provide a natural source of fertiliser.

After a successful pilot, the next phase added five acres of seagrass and an acre of mangroves to the restoration plan. A series of workshops trained locals in repair and planting work. People from other parts of Puerto Rico came to learn and took the skills back to their own restoration projects. Hundreds of mangrove seedlings were raised in greenhouses at the University of Puerto Rico. The project’s success attracted more funders and a massive expansion is now planned, restoring 500 acres of badly degraded habitat in the eastern part of Jobos Bay, with the added challenge of hydrological works to restore the natural flow of water that has been altered by a road and canals serving two power stations.

Above: shallow seagrass meadows like this are very vulnerable to damage by outboard motors – after which they may take decades to recover

Building on the success at Jobos Bay, 11th Hour Racing is now helping The Ocean Foundation to start another restoration project in the famous Bioluminescent Bay – the brightest in the world – on the Puerto Rican island of Vieques. Again they’re working with a local organisation, Vieques Conservation & Historical Trust. Outside help is needed as the community has such limited resources that four years after the hurricanes, they are still struggling to rebuild their island’s only hospital.

‘The bay took quite a beating from the hurricanes in 2017,’ Scheelk says. ‘There was a lot of destruction at the mouth of the bay and it’s eroding away. The concern is that if it widens, the nutrient balance will be thrown off and the dinoflagellate plankton that causes the bioluminescence will get flushed out into the ocean. That would devastate the island’s economy as all the ecotourism is based around that bay.’

After securing the mouth of the bay with two acres of mangroves, and some seagrass if a permit is granted, the plan is to restore the mangroves all around the bay, about 50 acres in total. ‘11th Hour Racing provided vital funding at the very beginning and we leveraged that money to make the project happen, which is how we got to where we are today,’ Scheelk says. ‘And now they’re helping us in Vieques. It’s been a remarkable relationship.’

The snag with blue carbon projects, he explains, is that while the potential benefits are enormous it takes a very long time to get a project certified, which must happen before funders can receive tradable carbon credits in return for donations: ‘You won’t know how much carbon has been offset until long after the work has finished.’ Carbon sampling can’t be done for a decade after planting and full benefit may take a century. But a restored seagrass meadow can thrive for thousands, even hundreds of thousands of years. ‘Mangroves are a bit different but both species are very long-lived,’ he explains. ‘They can effectively store carbon forever.’

To calculate and offset your own personal or organisational carbon footprint by investing in blue carbon habitat restoration work, go to Oceanfdn.org/calculator and join The Ocean Foundation’s Seagrass Grow programme.

Click here for more information on 11th Hour Racing »

We invite you to read on and find out for yourself why Seahorse is the most highly-rated source in the world for anyone who is serious about their racing.

To read on simply SIGN up NOW

Take advantage of our very best subscription offer or order a single copy of this issue of Seahorse.

Online at:

www.seahorse.co.uk/shop and use the code TECH20

Or for iPad simply download the Seahorse App at the iTunes store