It’s not just the widespread introduction of hydraulically powered winches that led to the sweeping clean of once cluttered big boat deck layouts... it’s also down to the elegant systems which they are a part of

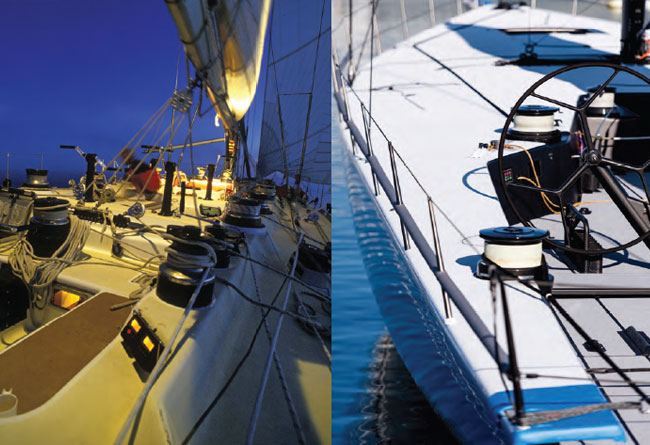

If a casual observer walking the dock were to see a new IRC maxi and an old IOR maxi from the 1990s alongside each other, they’ll probably see the Harken brand name on both sets of deck hardware. And they’re sure to notice the stark difference between the complex, cluttered deck plan of the IOR maxi and the clean, deceptively simple-looking deck plan of its modern IRC-rated equivalent. Where have all the winches and grinder pedestals gone? One of the most fundamental changes in the way we sail is the acceptance of powered systems. A side-by-side comparison of deck hardware shows just how far we’ve come.

Everything’s manual on the old IOR boat. You’ve got six pedestals and upwards of 20 winches – every control line has its own dedicated winch. Most of the time, each winch essentially functions as a heavy, expensive rope clutch. Tacking speed is determined not just by how quickly the grinders and trimmers can sheet the sails in, but also by the speed at which the rest of the crew can scramble across and around all those trip hazards to reach the new weather rail.

Compare that with the clutter-free deck of a modern IRC maxi – the one in the picture is a recently launched Botín 85, the first in a new generation of maxi racers. Where have all the winches gone? There are actually more sail and rig controls than there were on the IOR boat, but only eight winches in total, which is the practical minimum you can get away with if you want full racing functionality. But that doesn’t mean the deck hardware is any less important than it used to be.

‘Deck layouts are obviously cleaner. And the boats are much easier for crews to move around and push harder. But the boats certainly aren’t simpler’, says Mark Wiss, Harken’s director, Global Grand Prix and Custom Yacht Sales. ‘If anything, there are more adjustments and much higher loads to manage. These boats are more complex than ever.’

‘We involved Harken early on when we were looking at the initial design proposal,’ says Terry Halpin, the owner’s rep for the Botín 85 build project. ‘Botín had given us load estimates so we asked Harken for equipment proposals to work out how to handle the estimated loads: here’s what we’d like to do, how do you think we should go about it?

In many ways the new IRC maxi looks like a scaled-up TP52 but in one crucial way it’s a very different boat. Almost everything is powered by hydraulics, with 225 metres of hose running under the deck and inside the spars. Each of those eight winches is used for multiple trimming jobs and many of the lines that would traditionally be controlled by winches on deck are adjusted by hydraulic cylinders down below.

The decision to go completely hydraulic was driven by the IRC rating system, which offers several clear-cut options: rig controls can be declared as fully manual, or manual with a powered backstay, but for anything more than that you need to declare fully powered running rigging. If you add some powered hydraulic elements and keep others manual, you get the same rating adjustment as you would for a fully hydraulic yacht so there’s no point in doing things by halves.

‘There’s a lot going on under the deck with technology derived and developed from the 52s and 72s,’ Halpin explains. ‘The benefits include lowering the vertical centre of gravity, combining purchases and having less reliance on ropes. Even the mainsheet traveller is a single ram rather than two rope purchases. The jib lead controls, up-down and transverse, are also rams. Only the reelers are still manual, to prevent overload and damage.’

Some of the loads involved are remarkable. The headstay can be tensioned at up to 22 tonnes, which is more than most modern 100- footers can manage, even with hydraulics. ‘The headstay and jib cunningham are both anchored to the same chainplate,’ Halpin says. ‘When structured luff technology matured for headsails we were already building, so those elements had to be designed in. We needed a more powerful cylinder for the jib cunningham to handle the expected increased loading but that wasn’t a problem, Harken just supplied a bigger one.’ With a comprehensive range of deck gear and hydraulic equipment already optimised for grand prix racing, a larger unit was delivered in short order.

Photography:

RICK TOMLINSON

CORY SILKEN PHOTOGRAPHY

Most of the mechanical deck gear and hydraulics are semi-custom, built to order. ‘Most of the blocks on board are Harken V-blocks,’ says Harken’s Skip Mattos. ‘The most efficient block we’ve ever made is a stock product.’ The hydraulic systems use Harken’s standard-spec pumps, hoses and titanium Grand Prix cylinders, but the stroke lengths and integral load sensors are custom made.

A lot of effort has been made to reduce the weight of the valves and the programming logic that controls this finely tuned system is unique – and there’s a lot of competitive advantage in that side of things. Harken’s engineers worked alongside a leading specialist, Alan Severns of Marine Hydraulic Consultancy. Weight reduction is one reason to have fewer winches on board; the other reason is that every extra winch makes the programming logic more complex.

There are multiple trimming stations for every winch, each with its own data read-out. Load sensors inside the winches automatically determine the most efficient gear to use. The reduced gearing of the primaries is a key innovation, enabling the crew to do a complete gybe in first gear with the big kite up. Another novel feature is the take-up system for recovering offwind sails, powered by a hydraulic motor.

The hydraulic outhaul system is a further innovation. You might expect it to be mounted inside the boom, but not at the outboard end. This does put a bit of weight into the boom end that would otherwise be near the gooseneck or under the deck, but as Halpin explains, it eliminates the stretch of a rope outhaul and the inevitable compression loads of any system at the inboard end of the boom.

The result of all this engineering is a super-clean boat with all the tools needed for all manoeuvres – and it’s remarkably nimble too, probably more so than the Maxi72s, even though they’re smaller. ‘The only limit on the speed of a tack is how quickly the trimmers can react,’ Mattos says. ‘With a day racer like this, the goal is to keep things simple. Which is not to say that it isn’t clever. The line speeds can be set to automatically go faster when the boat is sailing downwind and slower when it’s going upwind.’

The maximum line speeds are carefully limited for safety. ‘We’ve reached terminal velocity for gybing and hoisting,’ Mattos says, ‘and also for spinnaker recovery. There’s too much risk of breaking things if it’s too fast or powerful. The hydraulics does the work, not the thinking.’

‘Most members of our team have a lot of experience but for many of them going 100 per cent hydraulic is new and they have to get used to the sheer power of it,’ Halpin says. ‘The only way to gauge the load while trimming is by using line markers and load sensor read-outs. The hydraulic system is very complex and there are a lot of read-outs: seven displays on the mast, displays at each of the trimming stations, and so on.’

This new style of hydraulic-powered sailing has interesting implications. Crew sizes might remain the same – you still need weight on the weather rail – but roles will change. Specialist grinders are no longer needed; you can have more trimmers instead. ‘It allows us to focus on crew skill sets that keep the boat at optimum performance for more of the time,’ Halpin says. ‘And when someone can’t sail with us due to illness or a conflict, rather than bring new people into the team we move people around. They get to step up to a role that they might not have every day.’

There are thorny questions for handicap systems and class associations to address. How do you deliver equitable ratings for powered and non-powered yachts? And is it fair to penalise things like hydraulic winches and backstay adjusters while allowing other hydraulic control systems that were historically manual? But there’s also a huge amount of potential. ‘From a pure power standpoint, hydraulic deck gear can go a long way to closing the gender gap,’ Mattos says.

For Harken, though, the manual versus powered debate is beside the point. ‘We respond to new boats by developing new technology,’ says Harken’s Mark Wiss. ‘We loved to see all those Harken winches up on deck but we’re not wed to any particular technology or era. We’re wed to being at the front of the way sailors want to sail.’

Click here for more information on Harken »

We invite you to read on and find out for yourself why Seahorse is the most highly-rated source in the world for anyone who is serious about their racing.

To read on simply SIGN up NOW

Take advantage of our very best subscription offer or order a single copy of this issue of Seahorse.

Online at:

www.seahorse.co.uk/shop and use the code TECH20

Or for iPad simply download the Seahorse App at the iTunes store