As GEOFF STOCK explains, if you’re going to drive a boat to its limits – you’ll need to know where its limits are…

Custom racing boatbuilders such as Green Marine succeed and prosper according to the quality and rigour of their R&D programmes. Mostly, our efforts have targeted the development of reliable process methods and the application of the latest materials and techniques to the boats we build. But increasingly over the past seven or eight years we have taken on the responsibility for structural engineering, and our efforts have been directed at the more general goal of building more reliable racing yachts.

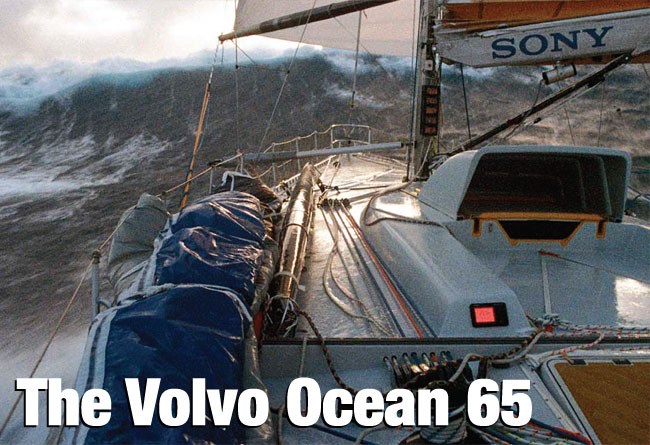

So, in June 2012, when presented with the task of leading the construction of the new Volvo Ocean 65 fleet, our first priority was to define the structural imperatives of the project. In the spirit of the Volvo Ocean Race itself, we put in place a programme that we hope will make a lasting contribution to the safety of ocean racing.

There is an inherent conflict between the performance and the strength of a yacht. The line between a racing boat being light enough and strong enough is not as sharp as we’d like; so with every project a decision must be made regarding how ‘close to the sun’ the structural engineers should fly. Twentyfive years ago race organisers decided that as far as boat structures were concerned they would make the ABS scantling guidelines the lower limit. This simplified the work of engineers considerably; their objective became a matter of getting the lightest boat possible throughout ABS plan approval. The ABS guidelines have long been replaced by ISO and GL, but the principle is the same: engineers work to a set level.

For most custom yacht projects that level is decided by the owner with advice from the architect and builder; and usually it is simply an agreement as to which classification rules are to be used. But for the more extreme projects this ‘call’ is a matter of judgement and experience rather than pure engineering. The VO65 is a boat that will race in inhospitable conditions and far from shore; the crews will push their boats hard and the consequences of structural failure can be serious. Green Marine worked with a group of racing yacht engineers who were able to bring 30 years’ experience of Whitbread and Volvo racing to bear on the issue of setting the strength level for the VO65. Clearly that level had to be significantly stronger than previous generations of Volvo Ocean Race boats; and in fact we settled on levels well in excess of ISO and GL requirements as well.

Though we set out to build a very robust boat, no one ever considered that the new VO65 should or could be unbreakable – a point that is made on page 1 of the Owners’ Manual. The speeds attained by modern racing yachts, coupled with the intensity with which sailors drive their boats, make hull slamming a real concern for both hull shell integrity and the longevity of a yacht’s internal structure. The VO65 is a high-performance racing yacht and there will be times when crews will have to ‘throttle back’ to preserve their boat. In fact, racing crews have always had to exercise seamanshipand experience to look after their boats; and this rather obvious fact was the starting point for the R&D programme that we refer to as the Structural Feedback System.

It’s one thing for a group of engineers to make a judgement as to how strong a boat should be – it is quite another for the crew to know what it feels like when their boat is close to its limits. To date we are not able to give crews a clear line up to which they can push their boats without concern; and even if there were a clear line, it would be expressed in water pressure head or acceleration. To a large extent we are currently relying on engineers’ judgement being sufficiently in excess of what sailors find acceptable.

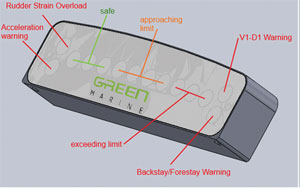

The task we have set is to see if, during the course of the Volvo Ocean Race, we can develop a system that will display a visual warning of when the boat is close to its design limits. To the best of our knowledge this is not something that currently exists; we are aiming for a system that analyses the behaviour of a boat and indicates the level to which the hull is being stressed while slamming from wave to wave at high speed.

In June 2012 we recognised that the new one-design fleet of Volvo Ocean racing yachts would be the perfect platform on which to gather data and develop a system that would eventually be of use to all racing yachts. But the challenges involved are not trivial. It is easy enough to collect the data and to install an LED array to indicate loading. The technical difficulty is in analysing the many strands of data input and converting that into a single piece of data output that is sufficiently meaningful for the crew to act upon.

In June 2012 we recognised that the new one-design fleet of Volvo Ocean racing yachts would be the perfect platform on which to gather data and develop a system that would eventually be of use to all racing yachts. But the challenges involved are not trivial. It is easy enough to collect the data and to install an LED array to indicate loading. The technical difficulty is in analysing the many strands of data input and converting that into a single piece of data output that is sufficiently meaningful for the crew to act upon.

To get the project off the ground we have installed on each VO65 a set of accelerometers and a data logging system that measures and records the accelerations of the boat in six axes: up/down, fore/aft, port/starboard, roll, pitch and yaw. We are logging the movement of the boats through the sea and relating this data to environmental information, rudder angle, keel ram position and rig loads. The output from the system will be displayed in real time on an LED panel mounted in the cockpit between the companionways. The panel houses a series of lights that progress from green to amber as the slamming loads approach the design limits; and then to red when safe working load is exceeded. The intention is to give the crew a clear comparison between the slamming loads being applied to the hull and the slamming loads that the boat has been designed to withstand.

In reality it will take time for our technical team to combine the angular and vertical accelerations in such a way that the single line output is trusted and used by crews. Structural engineers can analyse data and relate this to the design pressures used for hull shell calculations, but this remains academic unless their data and calculations can also be related to anecdotal evidence from sailors. It is vital that we get input from experienced oceanracing crews to calibrate what is normal and what is exceptional when it comes to hull slamming.

In reality it will take time for our technical team to combine the angular and vertical accelerations in such a way that the single line output is trusted and used by crews. Structural engineers can analyse data and relate this to the design pressures used for hull shell calculations, but this remains academic unless their data and calculations can also be related to anecdotal evidence from sailors. It is vital that we get input from experienced oceanracing crews to calibrate what is normal and what is exceptional when it comes to hull slamming.

We are mixing judgement, engineering and experience and it will take time to generate information to which both engineers and sailors can relate. We don’t think there has ever been a better opportunity to develop a structural feedback system than by working with the VO65 one-design fleet in the 2014-2015 Volvo Ocean Race. So to the 60 or so racing sailors and their support crews (all avid Seahorse readers, we assume) we look forward to your collaboration and support in this bid to make ocean racing a safer sport.

Click here for more information on Green Marine »

We invite you to read on and find out for yourself why Seahorse is the most highly-rated source in the world for anyone who is serious about their racing.

To read on simply SIGN up NOW

Take advantage of our very best subscription offer or order a single copy of this issue of Seahorse.

Online at:

www.seahorse.co.uk/shop and use the code TECH20

Or for iPad simply download the Seahorse App at the iTunes store